Helga Joergens The Art of Becoming

- Hinton Magazine

- Sep 29, 2025

- 18 min read

There is an otherworldly stillness to Helga Joergens. She sits with the quiet command of someone who has spent a lifetime listening to silence until it began to speak back. In her presence, the language of art expands. Charcoal is no longer a material but a memory of fire. Oil paint becomes a slow unfolding of light. Paper is not a surface but a stage waiting for its story.

Helga began as an observer of art, a student tracing the movements of those who came before her. Yet observation was never enough. To understand the pulse of creation she had to cross the threshold and step into the making of it. What followed was not a single direction but a constellation. Surrealist portraits that unsettled the mirror. Etchings that bit into metal with acid and time. Linocuts that carried the rhythm of expressionist voices. Abstract works that seemed to breathe in colour. Conservation that taught her reverence for fragility.

Her practice is not about style. It is about surrender. Helga does not command her work into being. She listens until the canvas tells her what it requires. That patience has given her art a rare intimacy. Each piece feels like a private conversation, the kind that changes you without asking permission.

For Hinton Magazine’s September cover, Helga opens her world with a candour that feels both delicate and unflinching. She speaks of doubt and discovery, of leaving and returning, of finding freedom in the smallest marks on a page. She reminds us that true artistry is not spectacle but devotion, a steady act of trust in what waits beyond the blank space.

After years immersed in academia, what was the moment — or the silence between moments — that told you it was time to become the artist rather than the observer?

During my studies of History of Art at Göttingen University in Germany, I wanted to be closer to the artists, whom I studied, and intended to experience some of the challenges they had faced. I found that I could understand works of art better if I did art myself. That is why I studied life and portrait drawing from life models in classes offered by the university. Unfortunately, I did not keep those drawings when moving to England in 1990.

However, two self-portraits of 1972, painted during the time before my university studies, remain: Self-Portrait and Surrealist Self-Portrait.

Left: Self-Portrait, 1972, Oil on cardboard, Right: Study for Self-Portrait, 1972, Graphite on paper

The painting Self-Portrait was prepared with a pencil drawing in the same size. Whereas the drawing represents a pure observation of my face in the mirror, the oil painting contains some surrealist features like the colouring in blue and green, the development of possible veins in my neck and chest into a tree branch and the addition of purple and green blood vessels in both eyes. The black surroundings and the pale light strengthen the expression and let the face appear rather eerie.

Left: First Study of my Face for a Surrealist Self-Portrait, Graphite on paper

Right: On verso of the same sheet of paper: Outlines for a Surrealist Self-Portrait, Graphite on paper

The Surrealist Self-Portrait was prepared using two pencil studies. In the First Study for a Surrealist Self-Portrait, I explored my own face directly from the front. You can see a young face in its outlines. I then turned the sheet over and, holding the paper to the window, traced the outer contour on to the back of the sheet and drew the chin area narrower and the eyes smaller which made the face appear older. The composition and details of the oil painting were already decided in the drawing. This was necessary as, because oil paint dries so slowly, you need to know exactly where each colour should go even if the final choice of colour is made during the painting process.

The curly hair and skin pattern with their cool yellow and blue colours denaturalize the head. On the forehead you can see another face representing the thoughts of the main head. The head and neck seem to have turned Into a sculpture which stands in a vast landscape at night. I enjoyed playing with shapes and forms, starting with my familiar face and transforming it into a painting far removed from the first rendering of my features but containing a new expression of its own.

Intaglio Prints: Different Types of Etchings

Intaglio printing means printing from incised lines or shapes in a metal plate. However, other substrates like glass can also be used.

I was fascinated by etchings which I had seen used with great mastery by Rembrandt van Rijn. Moreover, I researched printing techniques in general and decided that I would both understand and identify the techniques artists used better if I learned some printing techniques myself. Therefore, I enrolled on intaglio printing courses, which included etching techniques, to explore the various options and ways of expressing myself in this wonderful medium.

Here are three intaglio prints in which different techniques were used:

Left: Tree, Etching and aquatint in brown on paper

Right: Clean zinc plate for Tree

In Tree, you can see the lines being created as etchings, i.e., the lines were incised with an etching needle into a protective resin with which the zinc plate, right, was covered during the etching process, when the protected plate was immersed in an acid bath. The line drawing had removed the resin and the acid etched the lines into the plate. The two tones of shading were created with a technique called aquatint: A fine resin dust (called rosin) is sprinkled on to the plate and then adhered to the plate by controlled heating. The dust grain stops the acid from biting but where there is no dust, the acid etches into the plate. The light areas are successively covered with protective resin. Repeated immersion in the acid bath darkens the tone. The finer the rosin dust, the more even the tone. After etching, all resin is removed with methylated spirit or denaturalised alcohol. With a roller, the printing ink is applied to the plate which is then cleaned so that only the etched areas are filled with ink, and the image can be printed on paper.

The plate shows the picture as a mirror image, something that has to be considered when drawing onto it.

In View through Windows, you can see that the grain of the aquatint tones is coarser than the one of Tree because the rosin dust contains larger particles.

The next print was created using the technique of soft-ground etching. A special softer ground is applied to the plate, which contains fat to make it soft and sticky. The image is created by putting a thin sheet of paper loosely onto the grounded plate and drawing on the paper. By lifting the paper off, the area of the soft-ground, where the drawing is situated, is pulled off as it adheres to the paper. The exposed areas will let the acid etch into the plate to create an image which looks like a drawing.

Below, you see the soft-ground etching Boat under Bridge printed in brown ink and highlighted with watercolour in order to create a glowing atmosphere.

The zinc plate shows the areas of drawing lifted off by the drawing paper which were then etched into the plate by the acid. Shiny areas will be printed lighter and rougher ones darker as they carry more ink. There are some traces of printing ink left on the plate.

Below is one of three drawings on semi-transparent tracing paper for Boat under Bridge. The first illustration shows the front containing the pencil drawing and a correction in red. The second one reveals the reverse side showing the light brown soft-ground which was lifted off the plate.

Linocut

At the beginning of the 20th century, the German Expressionists - artists who wanted to express their feelings rather than the real world - rediscovered the woodcut, a technique which was used in medieval times before engravings were invented and superseded the production of prints.

As I could not carve woodcuts, I used the next best thing: lino printing. You take a sheet of linoleum and carve lines and shapes into it with special, inexpensive knives, V-shaped chisels or gouges. In contrast to intaglio printing, where you print the incised lines and shapes, with the linocut, the areas which stand proud and have not been cut, carry the printing ink.

Monument and Lightning shows the monument of a standing figure standing in dramatic bright light while being struck by lightning.

After printing several copies of this image, I used the imprints, which were not so successful because they were unclear or the colour was not very saturated, and created the following collage:

This picture contains a more complex variety of patterns and rhythms making the work more exciting than the original linocut.

Can you remember the first piece you created where you thought: this isn't an exercise anymore — this is my voice speaking?

I had learnt in the art classes at school with my very inspirational teacher, Professor Hans Joachim Beyer, to start a picture with confidence with the first stroke of a pencil or a brush. You then let your inspiration take over and discover that every colour or line you put down, asks for another one to follow.

For example, here are two pictures the compositions of which were drawn by Professor Beyer on the blackboard, and we had to copy them and fill the colours in. So, the two following works are not my arrangement but I learnt how to create a composition with abstract means:

Left: Composition in Warm Tones, Tempera on paper, Right: Composition in Cool Tones, Tempera on paper

I also learnt from him how to handle colour through colour painting exercises:

Left: Exercise: Tonal Scales in Blue, Yellow and Red, Tempera on paper, Right: Colour Exercise: Planet, Tempera on Paper

In Exercise: Tonal Scales in Blue, Yellow and Red, the general structure was given, and the colours were my choice. In Colour Exercise: Planet, the brief was only to draw a circle and create the effect of three-dimensionality by using colours. Exercises like these heightened my understanding of colour and colour perspective.

Based on these exercises, I painted the following picture: Two Mountains and Moons. The mountain in warmer colours, left, is positioned in front of the mountain in cooler colours, right. However, I am playing with reality in two ways, firstly, the mountain on the left should be bigger than the one on the right because it is in front but I wanted to move into Surrealism. The second, even more clearly surrealist quality is the fact that there are two moons in the picture: the larger one behind the smaller mountain and the smaller moon behind the higher mountain. This is intended to create surprise and puzzle the viewer.

One could say that this painting was the first one on the road to finding my own individual voice.

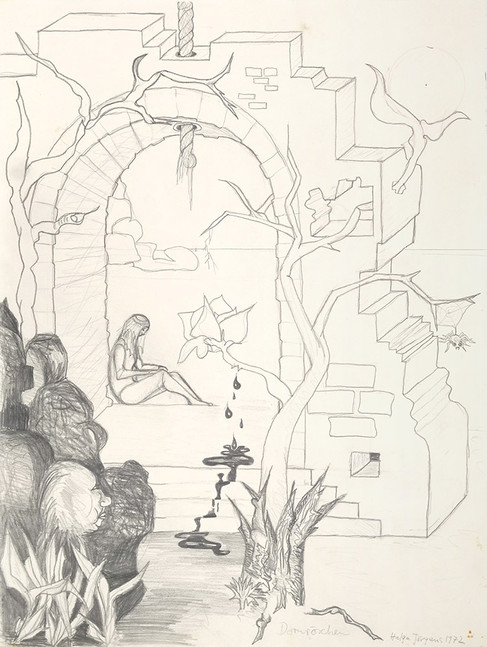

The truly first self-directed work happened early on in 1972 with my surrealist pen and ink drawings because nobody, as far as I knew, drew in that way. Here are two examples: Surrealist Calla and Fantasia with Bird.

I had been inspired by the prints of the artist, Hans Sünderhauf, who came from Berlin and lived for a few years in my home town of Jever in northern Germany, before he returned to Berlin. He taught at the local grammar school and, together with other students, I visited him in his studio and saw his work. It was exciting to visit the studio of an artist and to see his art in the flesh rather than in reproductions. His woodcuts, which I saw in his studio, were combinations of discordant items like birds and faces, positioned next to each other or on top of each other. His work represented an artistic freedom to paint or draw whatever you wanted. So, I tried it for myself but in a very different way.

When I was five years old, I broke off the long and narrow fruit of a Calla flower, which my mother was very proud of, because I regarded it as a worm. As I thought it to be dangerous to the flower, I wanted to free the flower from it. In 1972, when drawing my mother’s Calla, I remembered my earlier association of the Calla’s fruit with a worm. For fun, I changed the flowers into human and animal forms. I very much enjoyed this play with metamorphosis and the variety of images which I could create in order to make the picture interesting.

Walking out of the lecture halls and into the studio, did you find freedom or fear in the blank page?

I found a feeling of freedom in a blank page. Through the exercises of copying those compositions of Professor Beyer, I developed a certain confidence in placing elements on to a blank page.

Creating gave me a feeling of boundless liberty. It is very exhilarating. You enter into a different sphere and there seem to be only the picture and you in dialogue at that moment. Nothing else seems to matter.

The black pen and ink drawing on paper, Fantasia with Bird, belongs to a group of works in which I started the composition with wide sweeping lines and then worked out all the details as I went along. It was almost a feeling of story-telling. One area developed out of another, and the aim was to create as many different zones as possible which were full of surprises because they were different in scale and their content did not match. Unusual also is the fact that the centre is empty. The normal expectation is that the most important things happen towards the middle of a picture but not so here. I deliberately broke with this tradition. Surprise and fun were at the heart of this work.

You’ve spoken about your fascination with Surrealism — when theory turned into practice, how did that influence evolve in your own hands?

Surrealism gave me a sense of freedom to draw and paint whatever I felt like without any restrictions. There was no criticism of ,”This does not fit together”, or “This is not right” or, “This is not real”. There was no right or wrong. However, I soon found out that, although there was no place for adhering to a general logic like something appearing realistic in the normal sense, each picture has its own logic which I have to follow. It is the logic of composition, i.e., the relationship between the individual parts of an artwork to each other and to the whole work. If you talk about painting or drawing, the parts need to relate to each other in a satisfying way.

That is what I was and still am aware of. I call it, “The picture tells me what it needs and how I have to progress with it.” If I put down one colour, I need to add a different one to enhance the first one. I can be using bright colours and create a loud, lively and fast-moving effect. Or I can choose subtle tones and fine colour gradations to create a calm and soothing effect.

The surrealist drawings were followed by surrealist paintings in oil.

The first one was Sleeping Beauty, 1972.

The starting point for this painting was my pencil drawing of a rose from life which was then modified for the painting’s context:

Left: Rose, 1972, Graphite on paper, Right: Drawing for Sleeping Beauty, 1972, Graphite on paper

The complex composition of the painting was first drawn out in detail ( see above), transferred to the substrate and then painted.

The English title Sleeping Beauty, does not capture the German Title, Dornröschen, which means little ‘thorny little rose’. Like Sleeping Beauty in English, Dornröschen is the German title of Grimm’s fairy tale. However, the topic of my picture was more inspired by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s poem Heidenröslein, in which a boy saw a beautiful rose growing on heathland. He first threatens the rose to pick her. Then, when she retorted that she would prick him, he picked her anyway. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heidenr%C3%B6slein)

In my painting, you see the rose large in the foreground and the girl, whom the rose represents, in the background. She is sitting in the cooling shade under an old and crumbling archway, situated in a desert. In the foreground left, amongst big dark stones, the head of an old man is lurking and observing her.

The picture is full of references to dangers which could threaten the girl but she sits quietly, deep in contemplation as if unaware of the dangers. Perhaps, this unawareness protects her? Therefore, the message of this picture is not bleak but hopeful.

There are plenty of surrealist breaks with reality like the rose growing out of a tree trunk culminating in the top right with opening leaves which do not contain a bud or a flower.

Many artists spend years unlearning the structures they were taught. Did you ever feel you had to rebel against your academic training to find your instincts?

As I did not study Art at university but History of Art, I had the freedom to develop my art without any rebellion. Although I did not study practical art, I learnt so much about art and also its practical aspects through my research into different areas in the field from medieval to contemporary art. I enjoyed the freedom to choose between academic learning and free creating without any rebellion. I attended formal classes including life drawing classes and portrait drawing classes because I wanted to learn these academic skills.

Teaching History of Art and Design on the level of Further and Higher Education analysing and deconstructing a large variety of art and design furthered my knowledge.

In the early days of working professionally, were you chasing a style, or letting the work teach you where to go?

After leaving university and working at public art galleries in Germany, I became more interested in abstract art. This interest was also furthered by my contact with the painter, David Lendrum, now my husband, whom I met in 1982. By that time, my surrealist phase was over because I had lost my inspiration in that field. It was time to move on.

No, I did not chase a style but let the work lead me where to go. That happened both with my surrealist pictures as well as with the abstract ones. In fact, I still paint and sculpt in this way. An artwork develops in the process of making it. This way of working has the advantage that each work is a new adventure with challenges that have to be met on the way.

This is the only method in which I can create The reason is that, if I chase a particular style or expression, I may get tight and seem to keep looking over my own shoulder, or in other words, I criticise everything that I am doing. Then my art becomes rigid and stiff and loses its flow.

Every artist confronts doubt in the early years — what was your relationship with confidence like when no one was watching?

The important thing is that when I paint or sculpt, there is a dialogue between me and the work while the outer world is excluded. So, while I create, there is confidence.

However, I experienced that after a time, I had used up my inspiration. Those were the times when I had to rest from my art and wait for new ideas and stopped painting and drawing. For example, in the 1990s, after moving to London and embarking on my teaching career. I concentrated so much on teaching that I actually forbade myself to paint. Eventually, I went back to my own art because the urge to create was too strong to suppress any longer and I have kept with it ever since.

This is a very good question. If I want to achieve something in particular, I may lose my confidence if a work does not come out as I anticipate it. However, when that happens, I have to put that particular picture aside and let it rest, normally out of view, for a while. When I get back to it, I normally have created different pictures in the meantime which gives me the distance to see the mistakes I made in the first place and correct them. In that process, it may happen that the picture changes completely but that is fine because the first effort led into an artistic cul-de-sac which I could not allow to remain.

Etching, painting, conservation — your practice spans disciplines. Did that variety exist from the beginning, or was it something you grew into?

It was something I grew into through my curiosity; curiosity of how I could express myself in diverse artistic disciplines which all contained different challenges. I had seen etchings and paintings mastered by the great artists of the past and wondered what I could do with different media and materials.

I started my artistic journey with drawing which is the most spontaneous way of expressing myself. My surrealist drawings developed, in a way, also out of doodling, which I loved doing at school, probably like most other pupils. The drawings developed into compositions in which different areas on the sheet of paper were given different meanings which flowed into each other.

My early oil paintings were planned meticulously with studies and a full-scale line drawing. For this, different techniques needed to be applied: drawing, copying and then painting in oil. As oil paint dries very slowly, there were waiting times involved in order to let the paint dry. Nowadays, I use a quick drying oil medium which dries the oil paint within a few days. Without it, it can take weeks for the paint to dry. The advantage of slow-drying paint is that you can mix it during painting for a longer period but if you want to paint fine details, you have to wait until certain passages have dried. While waiting, I started work on the development and preparation of other paintings making the most of the time.

My interest in paper conservation was initiated through a seminar at Göttingen University. It was about artistic techniques and was taught both by my professor, Dr. Karl Arndt, and a painting restorer of the Gallery of Old Master Paintings in near-by Kassel who also showed us the restoration studios there. When working at the public art Gallery, Kunsthalle Bremen in Germany, I was regularly in the studios of both the painting restorer and the paper conservator to learn about their work and their treatments of paintings and works on paper.

The early part of any creative life comes with compromise. What sacrifices did you make, and what didn’t you allow yourself to give up?

There were compromises on time as studying and later working for a living took up much time thus diminishing the opportunity to be creative myself. However, I kept going and found pockets of time to draw and paint.

Looking back now, what would you tell the Helga who had just stepped out of university, holding ambition in one hand and uncertainty in the other?

I would tell her now, looking back, “Don’t stop creating, keep going because the inspiration comes while doing it.” If you worry about making art, what to do and how to do it, you unsettle yourself and stop your creativity. I found that, if I kept going, new inspirations would flow during the creative process and through the involvement with the materials. The materials gave and give me inspiration: beautiful colours, brushes which lie nicely in my hand, lovely and responsive watercolour paper or a white primed canvas are promising and give me inspiration.

Or, for example, when I created charcoal drawings, the charcoal inspired me: its matt black colour, the texture of the naturally grown, charred little sticks – which is what charcoal is: burnt twigs - , the noise the charcoal makes when you pull it over the paper. The fine dust which settles on the substrate inspired me to smudge it or to push it around with a wet brush in order to create subtle shades of grey or add restrained watercolours to it.

Here are a few examples:

Left: Hidden Figure, 1984, Charcoal on paper, Right: Abstract Figure, 1983/4, Charcoal on paper

While the drawing Hidden Figure shows line drawing as well as gentle smudging on the figure and darker smudging on the billowing curtain on the left, in Abstract Figure, the line drawing is combined with using lighter pressure on the charcoal sticks in order to create lighter or darker shading.

Left: Structure, 1983, Charcoal on paper, Right: House in Landscape, 1984, Black Conté crayon on paper

Whereas Structure was constructed solely with lines, in House in Landscape, I used black Conté crayons, which are sticks with a square cross-section made of powdered and compressed charcoal mixed with clay. They achieve a deeper and darker black than pure charcoal, and you can use their straight sides for drawing wide and straight lines.

Here are two examples in which I combine charcoal or black Conté crayon with subtle tones of watercolour.

In the first drawing, Flowing, I used a wet brush with a little red watercolour both in order to add another interest but also in order to push charcoal around and partly destroy the black lines to give the impression of moving water.

Below you see the drawing, Bridge, created with black Conté crayon combined with light shades of brown, blue and green watercolour which create the effect of transparency and make the picture shimmer.

At other times, I like to have a number of colours at my disposal, combine them into harmonious pictures or contrast them for exciting effects, painting or drawing over each other or scratching them out again to reveal the paint layer underneath.

The bright colouring of Morning Landscape was chosen to express the glory of a bright and sunny morning.

The technique of layering paint and scratching some of it away again in order to reveal the layers underneath was used in Flame, below. The bright and exuberant colours appear to give the picture a feeling of heat and of a flickering flame.

The interview with Helga Joergens unfolds like one of her paintings — layered, textured, and quietly defiant. She recalls her earliest experiments with Surrealism, her fascination with metamorphosis, and the thrill of discovering that confidence could be built one brushstroke at a time. She speaks of etching and linocut not as techniques but as new dialects of expression, each with its own demands and gifts.

There are pauses in her story, moments where teaching and life took precedence, but each return to the studio feels inevitable. Helga shares the honesty of those interruptions, admitting that inspiration does not arrive by waiting but by working, by placing one line after another until something unexpected emerges.

What lingers after the conversation is a sense of devotion — to curiosity, to process, to the dialogue between artist and material. Helga Joergens resists categories because she does not need them. She is an artist who trusts the unknown, who gives herself fully to the rhythm of creation, and who shows us that art at its most powerful is not about control but about listening.

Picture credits: Portraits of the artist: © 2025 David Lendrum, photographs of the artworks: © 2025 Helga Joergens

.png)

_edited.jpg)

Comments