Behind the Scenes with Sølve Sundsbø: The Real Elements of the 2026 Pirelli Calendar

- Hinton Magazine

- Aug 11, 2025

- 11 min read

Sølve Sundsbø is a creator who works in worlds rather than frames. His images are not simply taken; they are built—carefully, deliberately—until they carry both scale and intimacy. For the 2026 Pirelli Calendar, he has turned to the raw forces of the natural world, distilling them to their purest forms: earth, air, fire, and water. These elements are not imagined through digital trickery but captured in reality—photographed and filmed on location, then brought into a controlled studio environment using vast LED walls.

The calendar’s cast is as diverse and commanding as its vision—featuring luminaries such as Tilda Swinton, Gwendoline Christie, Irina Shayk, FKA Twigs, Venus Williams, Eva Herzigová, Susie Cave, Adria Arjona, Du Juan, Luisa Ranieri, and Isabella Rossellini. As Sundsbø explains, his aim was to capture “emotions, instincts and states of mind that’s central to human life”—longing for freedom, curiosity, imagination, and our deep connection to nature and time.

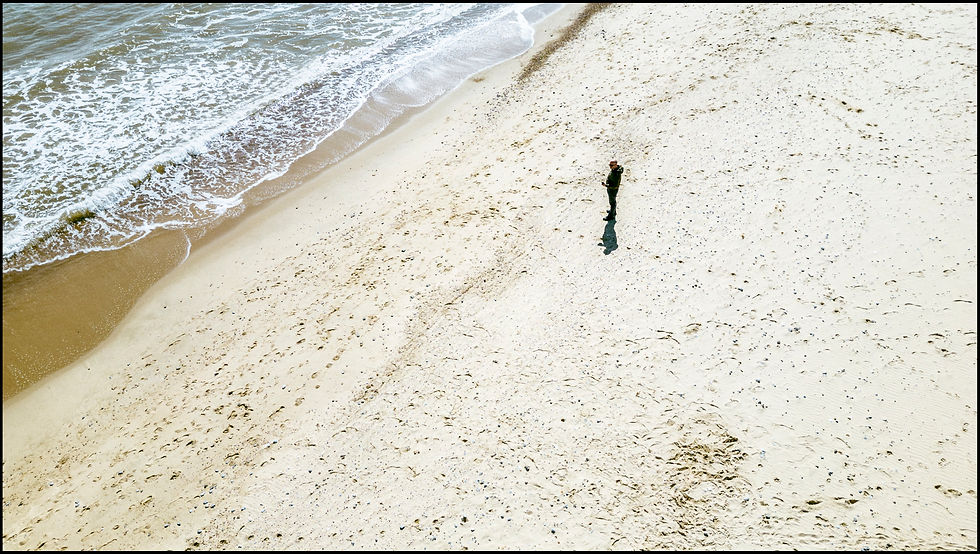

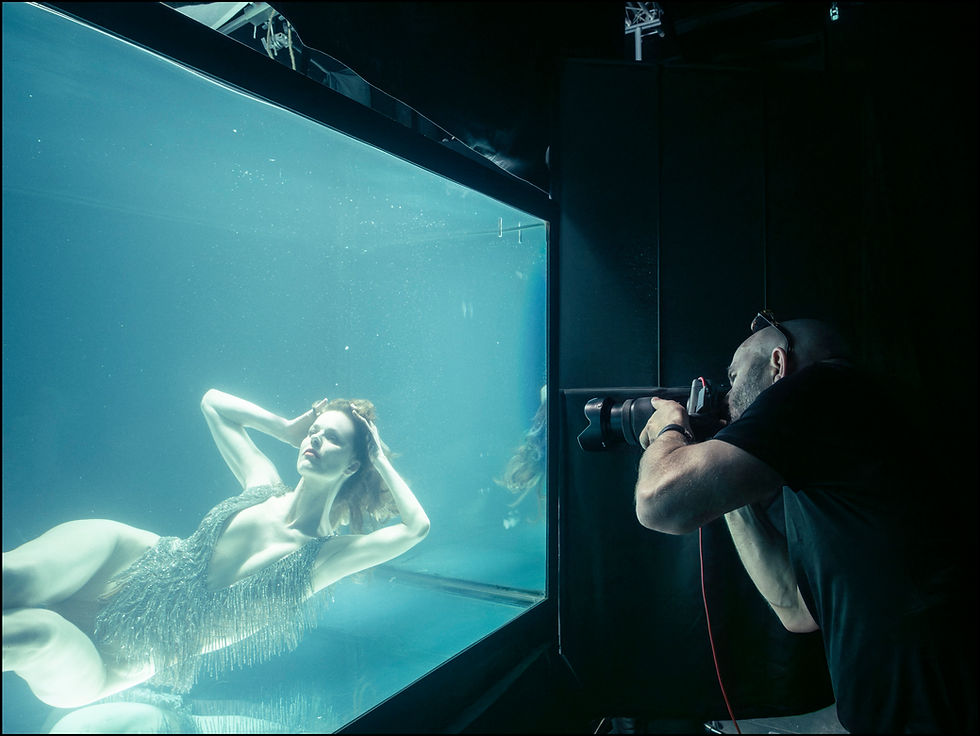

Alongside this conversation, we’re sharing a series of behind-the-scenes photographs from the making of the calendar—offering a rare look at the scale of the set, the precision of the craft, and the moments of trust between photographer and subject. These glimpses are just the beginning; the complete 2026 Pirelli Calendar will be revealed later in the year.

Curtis: I wanted to start by asking you about your inspiration behind the concept for next year's calendar.

Solve: When we first started talking about it, there were like two things. But the most sort of thing that stood in my mind was that we wanted to have a connection with nature. And I don't know if you overheard anything of this thing I said, but I'm going to pretend you didn't hear anything and just say the same things again. Because, you know, we wanted to have a connection with nature and I wanted to make it my own calendar. Because you think of Pirelli as an idea, you think: beautiful woman on a beach, right? But if you look at the history of the calendar it's actually quite a lot of variation in this. Well, you know, there's concepts like studio backgrounds, there's conceptual ballet ones, there is—there's all sorts of things that are happening in there. So you kind of think, okay, well, we're in this world where actually people have a very set idea about what it is, but the reality is that it's a lot of different things at the same time.

So there is a scope for having a connection with nature that isn't just going to a beach or going to an exotic location, but trying to put your own spin on that is quite difficult because, you know, reality is that you have all these people that you want to shoot and you want to have nature with it and then you have going to a location, or, you know, the weather, all those kinds of things.

So we thought, how can we make it exactly like I want it? By taking nature inside. So we went out, we went to Norfolk, we went to Essex, we photographed nature, we filmed nature, and then we brought it into the studio with this new technology. I don't know if you know about the wall, the volume, the XR screen. There's these huge, enormous LED screens where you basically can project, back-project whatever you want on it. And then you can kind of, all of a sudden, you can make an abstract natural environment and play with it and try to make it into something that isn't something that you necessarily have seen before.

So that’s what we started with that connection to nature. Taking nature and then bringing it inside. And then another element of this, which is quite important, is that we wanted to distill nature down to, you know, we didn’t want to have a beautiful meadow or a desert landscape or whatever. When I say we, I guess it’s me, but talking to people, so it’s not like a royal we—because it’s a team effort always. I wanted to distill nature down to sort of simplest forms. So the simplest forms of nature is the elements. And the elements, not in a sort of periodic table sort of context, but in a kind of more old way of thinking of the elements, like water, fire, wind, earth, those things. So when you work with fire, for instance, it’s easier if you’ve already photographed it and can back-project it rather than to put a studio on fire. So all of those things contributed to the fact that we ended up in West London in this amazing place on the Array Stage where you have these enormous LED screens where you can basically take nature in whichever way or form that you want and completely control the environment and make a picture of it.

Curtis: You mentioned about the team. How did you find working with them in terms of that? Did you feel they understood what you wanted to achieve to start with?

Solve: Yeah, because a lot of work goes into it in advance and when you work with the kind of people that we work with, there’s an element of trust that you want them to understand what you want to do. You want them to be part of it, so you talk to them, you show them pictures, you show them references, you sort of say, you know, could this work for you? In some cases it was like, that doesn’t really work for me, well then you have an alternative, and then you kind of make it into something that everyone’s interested in and willing to kind of you know, because it’s not easy to do these things. Hopefully it looks easy, but you know. But it’s not always easy to do it. And then, so if you have someone naked rolling around in sand, it’s not something that just sort of happens. It has to be something that person wants to do, and then in that process also, you always kind of now with digital photography, obviously, you can take a picture and you can show the picture and you can kind of work on it together because it is a team effort. It’s between the person you photograph, the photographer, and obviously all the people around. But that element of trust is super, super important.

Curtis: Do you get to put that team together?

Solve: Yeah, of course.

Curtis: What did you think of, when doing it, when imagining what you wanted, what were you hoping that the viewer is now going to perceive from that, from the images?

Solve: That’s a good question. I think—well, there’s different levels to that question, or different answer levels to that question. So one thing is obviously the first thing is I want them to understand that it’s part of this tradition of this calendar, but on another level I want them to see that it’s hopefully a new way of looking at the calendar. I want them to understand that there is a connection between—this sounds so cheesy. This is the thing. The thing with photography, compared to a photograph, it’s an emotion when you see it. If you start breaking down pictures into words, most pictures are quite silly, really, right? It’s a bit like dance. You know, like if you describe what someone is dancing, and they lift their arm up, and then they lift their leg. It doesn’t really work, right? Who said that to write about photography is like tap dancing about music? Writing about music is like tap dancing about poetry. It’s very hard to describe. It’s all about emotions. You want there to be an emotion. You want there to be some communication on an emotional level. Because photography isn’t a poem, it isn’t a short story, or isn’t any of those things. It’s like a little moment where the viewer has to imagine what happens before and after. You’ve got one moment in time, a split second in time, that leaves everything to the imagination. And hopefully the viewer will make up a story in their mind as to what happened. That’s what you want to achieve.

You also want when photography or art in general is at its absolutely best, is when you sort of open up a sort of window or a door to a world that the viewer hasn’t necessarily seen before. So, you know, if you go to an exhibition and you come out afterwards, you kind of think, oh, that looks—you know, you have an experience of the world through the lens or through the eyes of the person who’s presented the work you’ve just seen, and you kind of go, oh, that world is a bit like that, or this could be... that’s what you want to achieve. That’s very lofty ambitions.

Curtis: Do you think you’ve achieved that with this?

Solve: I can’t tell you that. And maybe I can in a year’s time, but when you’re in the middle of it, it’s impossible. With every project you work on (at least for me) find it really hard to look at it until like a year after, because when you’re in the middle of it, you’re concentrating on how to achieve it. And you can only see, oh I could have done that better, or this could be better, but at the same time, I have a very, very good feeling. But my job is not to be happy at this point. My job is to kind of try to make it better, always.

Curtis: You touched on the technology side a bit in the first point. How do you think you managed to keep the nature with the element of technology? Because technology with AI these things are looking more and more realistic. But you’ve not used AI, you’ve not used anything like that. So how do you think you’ve managed to—or the key importance of keeping that natural element with using technology?

Solve: Well, because we’ve gone out and, I guess, harvested nature through pictures and film and taken it inside. So the fact that it’s based on reality instead of AI makes it more real. I mean, it makes it real for me anyway. You know, maybe we are the only people who will—I mean, obviously now we’re talking about this, so people who read this will know. But even if that was the case, even if people say, oh, they’ve used AI—we know that we haven’t. Do you know what I mean?

Curtis: You know it’s all real.

Solve: Yeah.

Curtis: Which is a rarity at the moment.

Solve: Yeah. I mean, it’s so funny how it works, isn’t it? Now even the AI gets confused by itself because it’s harvesting AI images.

Curtis: How did you find working with the cast, the models?

Solve: I mean, these people are really special people. These are people with experiences who we have cast because I admire them for what they are doing in their careers. And I also happen to know quite a lot of them over years. So I know that these are people who, because like I said before, there’s a huge element of trust. So we shot Ava Herzog underwater. If you know anything about being underwater, you know you can’t breathe. You can’t hear. You can’t really see. And being underwater doesn’t make you look good, because your whole face floats up and your hair goes everywhere. You’re completely bewildered about where you are and what you’re doing. And to do that to someone, you need to know that that person will trust you and you have to deserve that trust. And that’s a huge pressure because you want that person to look amazing, right? And you want the picture to look amazing.

Curtis: How do you pitch that to them? To tell them that that’s what you want them to do?

Solve: Because if you’ve known someone for a long time, they know that you wouldn’t ask them unless you thought it would be good, right?

Curtis: So it comes down to trust?

Solve: Well, if you talk about football, if your coach says you should do that run, it’s like, why? Just trust me. If you trust your coach, you make that run. If not, you won’t do it.

Curtis: What would you say was the most challenging part of doing the whole—I mean, obviously, I know you’re not through it yet—but doing the whole calendar?

Solve: I think the biggest pressure is the pressure you put on yourself really, because you feel like you’re in a pantheon of great photographers through the time, so you don’t want to let the team down.

Curtis: It must be tough.

Solve: In real world terms, not really. If you have a better perspective, it’s just a pleasure, nothing but a pleasure.

Curtis: You mentioned in answer to a previous questions you wanted to create something new, maybe take it in a new direction moving forward, but every photographer is going to have their own style. Do you think you its possible to achieve uniqueness?

Solve: Yeah, I think it’s impossible to do something new, but you have to at least try to make something that feels personal. I think that’s the thing. I think it has to be personal.

Curtis: We’ve touched on it already, but with tech evolving, how important is it that you keep things natural like you have done?

Solve: Yeah, the thing is that the thing with this tech is that it makes things more, you could do probably a lot of this by shooting it on a blue screen or, you know, whatever. But here you actually react to it because you can see it. So it’s easier to compose a picture and to understand the emotion of the picture because you actually see it in front of you.

Curtis: Do you worry, specifically with AI, do you worry that that is going to make the realism obsolete in terms of feeling?

Solve: No, the opposite. I think it’s going to make reality even more luxurious.

Curtis: Could you elaborate?

Solve: Yeah, I mean, if you—let’s say if you’re a luxury brand, right? If you start using AI, it’s no longer luxury, is it? I mean, you know. So luxury brands thrive on something handmade, something special, something unique, and AI is all the opposites to that. It’s not unique, it’s not handmade, it’s not special, it’s something everyone can have. So I think that in one way it’s a bit like photography didn’t make paintings obsolete.

You know, everyone thought that, oh yeah, photography’s coming, painting is dead. In fact, it made paintings more special in a way. Because before, painting was photography. And then photography took a part of painting—like the quick portrait, for instance, is no longer a quick line drawing. But you know, it made painting more special.

So I think that AI is going to make reality in advertising even more valuable and special. And I don’t think that AI is not going to exist in that world. It already does. But for what I do, it will just be a tool. It will be a tool like Photoshop. I’m not opposed to it. I’ve just done a whole book. That’s just AI. But the AI is just trained on my pictures. So the training model is just things that I’ve done. It’s just on flowers. So we made flowers that don’t exist. And so I definitely think AI is a very valuable tool.

But for Pirelli, I don’t think it’s the right thing at the moment, at least. I think it makes it more special not to have it.

Curtis: Finally, what was your favourite part about it all?

Solve: Oh, my favourite part of it all?

Curtis: It’s probably tough to pick just one.

Solve: Yeah, I think it’s the whole experience, like a global thing, rather than a special moment. Maybe if you ask me in like 10 years I can pick it, but at the moment you’re immersed in it, so it’s a bit hard to see. So I have to say that the immersion in the whole thing is the best thing.

Under Sundsbø’s direction, the 2026 Pirelli Calendar becomes more than a sequence of images—it is a study in presence and authenticity. Every frame carries the textures of the real world, shaped by the discipline of meticulous planning and the willingness to let the elements speak for themselves. The calendar’s extraordinary cast embody the emotional and instinctual core Sundsbø sought to capture—states of mind as universal as longing, curiosity, and the desire for emancipation.

The behind-the-scenes moments included here capture the unpolished side of the process: the vast LED landscapes before the lights rise, the adjustments between takes, the quiet exchanges that ensure trust on both sides of the lens. They are fragments of a far larger vision—one that will be fully realised when the 2026 Pirelli Calendar is officially released later this year. Until then, these images offer a rare window into the making of something destined to leave its mark.

.png)

_edited.jpg)

Comments